Jammu and Kashmir: Killing of civilians sparks militancy fear

Siddharth Bindroo, 40, was on his way to a restaurant in Kashmir’s main city Srinagar when he received a call.

“Papa is dead,” said the caller – leaving Mr Bindroo, a noted endocrinologist in the region, shocked.

Some men allegedly entered their family-run medicine store on 5 October and shot his father, Makhan Lal Bindroo, thrice.

ML Bindroo, 68, was the son of Kashmir’s famous medical practitioner and pharmacist Rakeshwar Nath Bindroo. The family runs a famous pharmacy chain which is known for selling life-saving drugs in the region.

The Bindroos were among more than 800 families of Kashmiri-speaking Hindus – locally called Pandits – who chose to stay when hundreds of thousands of them fled for safety to other Indian cities during an armed insurgency in the Muslim majority-region in the 1990s. The militants, seeking independence from India, often targeted the minority Hindus and accused them of working with the security forces.

Now, a spate of killings of civilians in recent days in Indian-administered Kashmir has again led to widespread unease, particularly among the region’s religious minorities.

On the day ML Bindroo was killed, two other civilians were also murdered – a Hindu street vendor from the eastern state of Bihar and a Muslim cab driver, both of whom were fatally shot by unknown men. Earlier on 2 October, two Kashmiri Muslims were killed in a similar fashion.

Image caption,Siddharth Bindroo consoles his mother after she heard the news of the death of her husband

Barely two days later, assailants stormed a government-run school in Srinagar’s isolated Sangam area, killing the principal and a teacher – a Sikh and a Hindu.

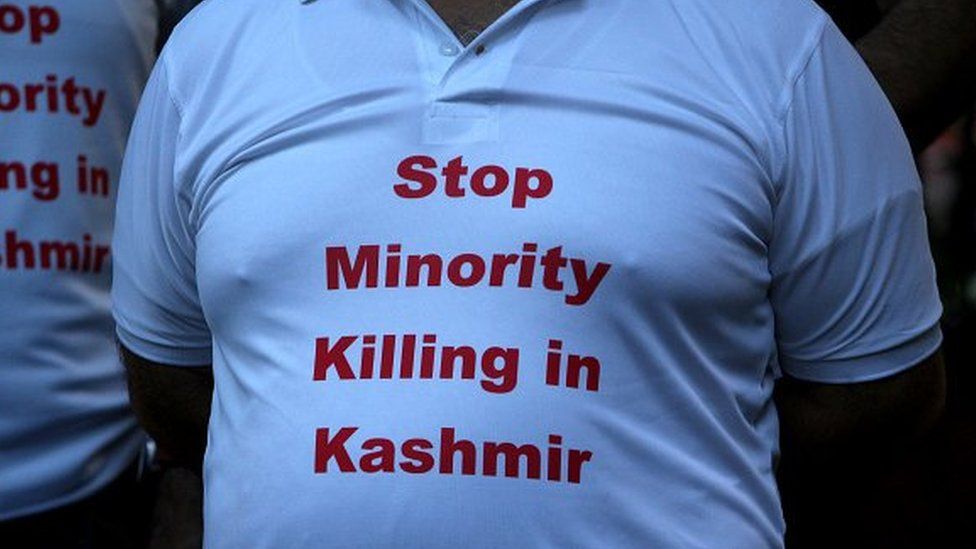

The spate of targeted killings has triggered widespread fear, especially among the minority communities of Kashmir, which has seen a decades-long armed insurgency against Delhi. Many Hindu families are now leaving the tense region, leading to comparisons with the situation in the 1990s.

It has also brought the government’s claims of peace into question.

Kashmir is claimed in full by both India and Pakistan, but ruled in parts by the nuclear-armed neighbours. Relations between the two countries have always been tense, but reached a new low when Delhi revoked the region’s special autonomy in 2019.

The move was followed by a months-long communications blockade and a slew of administrative changes, which locals say are aimed to bring demographic changes in India’s only Muslim-majority region.

Ramreshpal Singh, husband of Supinder Kour, the school principal killed last week, said he could not speak for two days after his wife’s death.

“I could not ask for the details about how she was killed,” Mr Singh said. “I saw my wife dead and everything else lost meaning for me.”

Police and eyewitnesses have confirmed that armed attackers barged into the school, summoned all staff members and asked for their identities. According to initial police reports, the principal and the teacher had been separated from the rest of the staff. They were later shot dead.

“Supinder was like my sister,” said her neighbour Majeed. “She was so generous that she had adopted a Muslim orphan girl and would spend part of her salary on her upkeep.”

The killings of ML Bindroo and Supinder Kour add to some of the targeted attacks on Kashmiri Pandits and Sikhs in the last two decades. In March 2000, unknown attackers shot dead more than 35 Sikhs in a village in Anantnag district. And in 2003, more than 20 Kashmiri Pandits were killed at Nadimarg, a remote village in Pulwama district.

The most recent murders – seven in a week – happened at a time when more than 70 ministers from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government took turns to visit Kashmir. The ministers were sent to highlight the “benefits of removing article 370” from the Indian constitution on 5 August 2019.

The article allowed the state a certain amount of autonomy – its own constitution, a separate flag and freedom to make laws. Foreign affairs, defence and communications remained the preserve of the central government.

But local politicians said the situation was far from normal, and some have compared it to the turmoil of the 1990s. Former Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti said the killings were “a loud rejoinder to the false claims of peace and normalcy”.

Kashmir’s police chief, Vijay Kumar, said that at least 28 civilians had been killed by suspected militants this year in Kashmir. “Out of 28, five persons belong to local Hindu and Sikh communities and two were non-local labourers,” Mr Kumar told reporters last week.

Although most of the victims were Muslims, the killing of people from minority communities this week has sparked fears of underlying religious tensions.

The Director-General of Jammu and Kashmir Police, Dilbagh Singh, said the killings were “an attempt to damage the communal harmony”.

Police say they have launched a search operation to arrest the attackers. According to official sources, hundreds of former militants and protesters, who are out on bail, have been called in for questioning.

But Kashmiri Pandits say they continue to live in fear. Many of them are considering leaving the region.

“Scores of Pandit families have left in recent days and many are planning to migrate,” said Sanjay Tickoo, 53, who heads an organisation that represents more than 5,000 Kashmiri Pandits living in the Valley.

“I am getting panicked calls from Pandit families. The authorities have removed me from my home in Srinagar and lodged me in a hotel. How can we live in such a frightening situation?” Mr Tickoo told the BBC.

The house of Bindroos in Srinagar too has been fortified from all sides. Even the walled apartments, inhabited by Kashmiri Pandit families who returned over the years under a government programme, now look desolate.

“Some families have left. We feel insecure. The government officials come here and assure us support when some incident happens. But can they secure all schools and offices?” a resident from one such camp said on the condition of anonymity.

It’s not just the Kashmiri Pandits who are anxious – fear and uncertainty has gripped the entire valley.

“The exodus of Pandits in 1990 was one tragedy and what followed was another one. There was a massive security crackdown of the whole population. I am afraid to even recall those days. That should not happen again,” said Muhammad Aslam, a carpenter, who lost his cousin during a cross-firing incident in 1991.

But not all Kashmiri Pandits want to leave. The Bindroos say they will stay back.

“We belong to Kashmir, we are Kashmiris and ML Bindroo’s blood runs through our veins,” says Shradha Bindroo, Makhan Lal Bindroo’s daughter.

Sidharth Bindroo agreed. He said that 90% of the mourners who visited the family after his father’s deaths were Muslims.

“I don’t think we have any reason to leave, I have my people here.”